The enteric nervous system is known as the body’s “second brain,” a vital communication center housed in spiderweb-like circuits within two layers of the gut lining. It helps to manage functions central to digestion, immunity, and mood.

It’s called the second brain because it’s made up of a collection of hundreds of millions of neurons and acts independently but in cooperation with the other branches of the autonomic nervous system. It coordinates several complex functions by using 30 different neurotransmitters. More than 90 percent of the body’s serotonin and about 50 percent of its dopamine are found in the gut.

At one level, the enteric nervous system (ENS) acts like a vehicle’s ignition system, providing a perfectly timed spark of energy for a chain reaction that powers the muscles to move food through the human digestive tract. It also maintains homeostasis, or balance, when our body experiences invaders—such as toxins, viruses, and parasites.

When ENS circuits get disrupted, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms—such as constipation, diarrhea, and pain—can follow. Sometimes, those symptoms are actually good news, however, as they mean that the ENS is at work expelling pathogens.

But when these symptoms become chronic (long-term), it can mystify patients and doctors. That mystery is attracting researchers to explore treatments that spur the ENS into proper action, which could help with diseases ranging from Crohn’s disease, colitis, and irritable bowel syndrome, to neurological ailments such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. It’s also being looked at for psychological conditions such as depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia.

An Incredible System

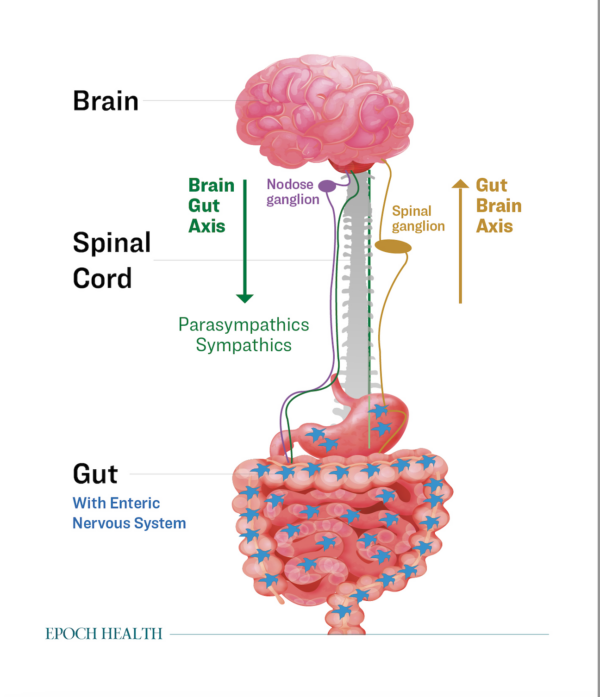

The ENS is sometimes considered an independent system but may also be classified within the peripheral nervous system, which is the nervous system beyond the brain and spinal cord.

Officially, the ENS is part of the autonomic nervous system, along with the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

The ENS’s key job is to push food through digestion, which includes sensing and evaluating what’s in the food.

“It can’t see what it’s going to get, so it has to be ready for anything. One day, you might eat steak and the next, just vegetables. It has a huge capacity to adapt,” Keith Sharkey, professor of physiology and pharmacology at the University of Calgary, told The Epoch Times.

“To make it more complicated, what you eat might not be free of germs. The gut is an outside organ, because we consume food from the outside, but it’s within our body and has to protect our body from toxins, contaminants, parasites, and unwanted bacteria. It does it very effectively most of the time.”

ENS cells can directly and indirectly sense and respond to cues from gut microbes and immune cells, which helps them to know when problems are developing.

When they do, they primarily lead to motility issues, meaning that they’re linked to peristalsis, the sequence of contractions that move food through the digestive tract. Unhealthy motility is food moving too fast, too slow, or moving backward.

The ENS manages the stomach, large intestine, small intestine, and more. It decides what gets stored and what gets excreted. It has to respond to what the body needs at any given moment and has a big influence on the rest of the body, including the brain. If you eat too close to bedtime, for example, the ENS tells your brain that the body is going to have a bunch of energy soon so it shouldn’t secrete melatonin and induce sleep.

For Health and Disease

Clinically speaking, the gut is a logical place to start for healing most any ailment, Dr. Scott Doughty, an integrative family practitioner with U.P. Holistic Medicine, told The Epoch Times.

That’s because the molecular body, including the energy sparking it to life, is made from the sun on our skin, the air that we breathe, and—most substantially—the food that we eat. If what we eat or drink is problematic, or we’re digesting it poorly, nearly any problem can follow.

Often, the key to restoring health starts with something as simple as taking a critical look at stress, which impairs digestion, or eating and drinking habits that aren’t serving us well.

“The gut is probably the most amenable to some basic changes that can improve the way a person functions,” Dr. Doughty said. Best of all, many of those changes don’t require a drug, he said.

Mechanism of Action

Peristalsis, that synchronized movement of contractions that moves food down your throat and through the 26-foot-long digestive tract, can be affected by countless conditions, imbalances, medications, injuries, and infections. Symptoms of problems include constipation, gas, diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, bloating, nausea, burping, acid reflux, and difficulty swallowing.

The neurons of the ENS wind through the tissues of the digestive tract like a web. Protecting this web is critical because it remains a controversial hypothesis about whether it can regenerate, Mr. Sharkey said.

Aging will cause enteric neurons to die off. This may explain in part why the elderly tend to suffer from motility issues such as constipation. But there are measures that we can take to improve our overall health that also appear to protect the ENS, particularly by taking advantage of its relationship with other parts of the nervous system.

For instance, dysbiosis—or an unhealthy balance of microbes in the gut—can also lead to impairment and changes that influence gut function and motility.

‘Rest and Digest’

The ENS cooperates closely with the other two branches of the autonomic nervous system—the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. This relationship allows the best use of resources depending on what we’re asking the body to do at any given moment.

While the work of the autonomic nervous system is automatic, it responds to whatever we do or communicate to it. For example, the ENS goes to work when we eat. Likewise, if we perceive something as threatening, we set the sympathetic nervous system into action.

The sympathetic nervous system manages our fight-or-flight reaction. It floods the body with certain hormones and gives us an increased heart rate to deliver oxygen to large muscles. It also asks the enteric nerves to inhibit digestion, which may otherwise slow us down. Some food takes a lot of energy to break down, and we also don’t really want to stop and relieve ourselves when we’re running away from a bear.

But that can create a lot of problems. We live in a time of chronic stress. And, unfortunately, our autonomic nervous system can’t tell the difference between immediate threats—such as a bear—and more distant threats—such as rising mortgage rates. If you feel stressed, scared, angry or worried, you’re telling your autonomic nervous system that there’s danger.

The parasympathetic nervous system is the sympathetic nervous system’s counter. This branch of the autonomic nervous system manages our “rest-and-digest” state and stimulates enteric nerves. When we feel calm and safe, the parasympathetic nervous system asks the ENS to restore digestion.

After a stressful event or threat, the nervous system normally comes back to homeostasis and digestion continues. If it doesn’t, there are things that we can do to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system and allow it to tell our ENS to restore gut function. This is an area of interest to researchers such as Mr. Sharkey, who see the potential in gut motility treatment through the ENS.

Influencing the Second Brain

As you might expect, the key to influencing the ENS is through the parasympathetic nervous system, and the key to this system is the vagus nerve. This long, winding nerve connects the brain to the heart, lungs, gut, and more. The vagus nerve is the key component of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Stimulating the vagus nerve can be as easy as calming your heart and mind. And if you do so, there are countless helpful consequences.

“If you stimulate the vagus nerve, it can produce an anti-inflammatory response in the body,” Mr. Sharkey said, giving one example of potential benefits.

One study in the Journal of Internal Medicine describes lipid mediator biosynthesis—a byproduct of vagal nerve stimulation—as having the same effect as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which reduce inflammation and decrease pain and fever.

In extreme cases, the vagus nerve can be stimulated using a device similar to a pacemaker that sends regular, mild pulses of electrical energy to the brain from the vagus nerve.

However, this is medically recommended only for seizures and treatment-resistant depression. Fortunately, there’s evidence that mindfulness activities, especially breathing techniques, can also stimulate the vagus nerve.

“This is why some people think yoga is beneficial. And there’s no question that yoga is beneficial,” Mr. Sharkey said. “There’s a huge number of studies that have demonstrated that.”

The vagus nerve can also be influenced indirectly through cognitive behavioral therapy, which works to change the way we think in order to calm symptoms of anxiety, panic, and fear.

From the Gut Up

What happens in the gut can make its way to the brain. While processed sugar can stimulate brain activity in a way that’s similar to addictive drugs, more wholesome foods can calm the brain and relax our mood. A diet consisting of whole, unprocessed foods with a healthy balance of protein, fat, and fiber is associated with stable blood sugar and mood improvements.

“Your gut dictates how you feel, and if you don’t realize that, you’re either asleep at the wheel or you aren’t getting drastic messaging that reminds you it’s a fact in basic biology,” Dr. Doughty said.

“Every day we’re accessing the enteric nervous system, and we’re doing so in rather indirect ways, but one of the more direct ways we can address it is with digestion and how it interacts with the rest of the system.”

In short, eat wholesome foods, keep calm, and carry on.